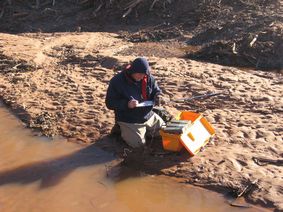

Volunteers seining in the tributary to the Arkansas River. Volunteers seining in the tributary to the Arkansas River. In previous blogs, I described the way we collect the bugs living at the bottom of the creek and the multi-day “fish school” that our staff members recently attended. What I learned at fish school is now invaluable during the summer months when we do another kind of collection: fish collections. Similar to the bug collections, we look for fish to find more information about how healthy a creek is. Certain kinds of bugs can tolerate pollution while others cannot. Fish are the same way; some can live in more polluted waters while others are not able to survive in those conditions. Every summer, the Blue Thumb staff conducts these fish collections in a designated area of the state, which rotates every four or five years. So, for example, if Oklahoma City creeks had collections this year, those creeks would not be fished again for another four years. This year, the primary area we are fishing is Cherokee County in the northeast, especially around the town of Tahlequah. This is an area with a lush, green natural environment, filled with trees, hills and creeks that run very clear through rural towns and over a creek bottom with lots of gravel and rocks. An exciting opportunity for contrast will be the few creeks we are also fishing in Lawton and Sulphur. We actually started this year’s fish collections in Muskogee, a much more urban environment than where most of this summer’s creeks will be found. This first creek, a tributary of the Arkansas River, runs through a residential area with a number of homes and has a close encounter with a nearby highway. When we arrived there, Kim, Jeri and I met up with Abigail Wright, our Blue Thumb volunteer who monitors the site as well as Sherry Davis, an intern working with the Conservation Commission for the summer. The collections always begin with a habitat assessment of the creek, with all of us walking 400 meters up the creek, taking note of many important factors, including bank vegetation, bank erosion, how deep the water is, what the creek bottom is made up of and what kind of habitat is available in the stream for aquatic organisms. After doing that, we return to the spot where the assessment ended and work our way back down the creek collecting fish. How exactly do we collect fish, you ask? While there are a number of ways that people can perform a fish collection, our collections with volunteers employ the use of a seine. A seine is “a fishing net that hangs vertically in the water, having floats at the upper edge and sinkers at the lower.” We typically use two of these, small and large, and choose one depending on the size and type of area we are seining. Kim leads the way, making decisions as we go along about which seine to use, which part of the stream to focus on, where to put the seine in, where to pull it up on the bank and other important steps along the way. One of the most important things to remember when seining is to keep that lower edge, the one with the sinkers, or “lead line,” on the bottom of the creek at all times. This way, fish can’t escape underneath the net as you’re moving forward. It’s also important to get the poles of the seine angled correctly, keeping the lead line end of the pole on the creek bottom, maintaining the right angle of the pole to keep the basket shape in the net and using the end of the pole to poke and prod banks of the creek to get the fish out of the roots and rocks that create habitat. Tributary to Arkansas collection was a lot of fun and gave us all a chance to encounter a number of fish as well as other wildlife, including a snake and turtle. Being in the creek on a hot summer day, especially when we were in areas with no canopy cover, gave me a good idea of what this kind of work can be like for those who do it all the time. It also provided a good contrast to the other creeks I would soon encounter, as this one was in a more urban setting, was more murky and more impacted by trash and human development than some of the creeks to come. Providing the starkest evidence of human impact was the long tunnel we had to seine through as it passed under the roadway above. Enough water ran through the tunnel that we were able to seine both sides of it and find evidence that even with that kind of concrete environment, organisms still live in the water there. For the fish collection as a whole, we found numerous sunfish (bluegill, longear and green) as well as mosquito fish and central stonerollers. For the second creek on our collection schedule, we travelled to Tahlequah. Cedar Hollow Creek feels about as far as you can get from an urban setting and human development. The creek is located in the J.T. Nickel Family and Nature Wildlife Preserve, owned by the Nature Conservancy. After we parked our vehicles and met up with Blue Thumb volunteers Gary and Irene Wickham, we walked into the woods to the monitoring site. Heading farther up the creek and deeper into the woods, the creek remained pretty shallow, just a trickle over the numerous rocks in many places. It’s a lovely and tranquil spot, very quiet, especially compared to being at a creek that runs along and under a highway. Even with the shallowness of the creek overall, there were some deeper pools that allowed for good seining and we found quite a few fish, including creek chub, orange throated darter and lots and lots of southern redbelly dace (there were many dace puns to be had all during the collection). More fish collections are happening and will continue over the next few weeks. Stay tuned for those stories. Same Blue Thumb time. Same Blue Thumb channel.

0 Comments

Water Quality Specialist, Wes Shockly is out in all kinds of weather checking on Oklahoma's water resources . Water Quality Specialist, Wes Shockly is out in all kinds of weather checking on Oklahoma's water resources . Over the past six months, there have been so many things to learn. Much of this job is new to me and has provided me the opportunity to find out about and experience many new things. One thing I have become more aware of is the Section 319 program, part of the federal Clean Water Act. This program provides money to states for initiatives that focus on water pollution and water quality, including our own Blue Thumb program, which is primarily funded by 319 money. The Clean Water Act and subsequent Section 319 program are part of a long history in this country of growing awareness and interest in environmental issues, including water quality and pollution. For more on that history, and what it has meant to us here in Oklahoma, we turn to Wes Shockley, one of our water quality monitoring specialists, a native of Oklahoma who has quite a bit of history himself with the Conservation Commission and the Water Quality Division. The turn of the twentieth century marked a time of explosive growth in industry. Many of these factories required large quantities of water, either for the manufacturing of their product or for the cleaning and cooling of their equipment. So it was only natural that these businesses were located near large supplies of fresh water. Perpetual containment of this waste water was not practical. The convenient answer was to simply return the water to its source in its new form, complete with oil and grease and a myriad of other chemical byproducts of the various manufacturing processes. This practice continued, principally without thought or regulation, for decades. In 1962, Rachel Carson authored Silent Spring. Her award winning work chronicled the effects of the pesticide DDT on a population of song birds and other wildlife and it spawned a national increased sensitivity to the natural world. Then, in 1969, the Cuyahoga River, in Ohio, caught fire. The river was so polluted at this point that its burning had become commonplace, but for some reason on this occasion, the story garnered local press coverage, complete with photos. Soon, a few big publications and news outlets picked up the story and it went national. Seemingly overnight, the entire country was metaphorically on fire with a new consciousness of and responsibility to the environment. This momentum continued to build and compelled President Nixon, on Dec. 2, 1970, to sign an executive order establishing the Environmental Protection Agency. (EPA). In 1972, amid growing public concern, congress passed the Clean Water Act (CWA), placing regulations on municipal and industrial dischargers and creating the NPDES permitting system, which was designed to track dischargers and monitor the quantity and quality of their effluent. The overarching goal of the CWA was that all surface waters of the U.S. should be fishable and swimmable. Good progress was made toward that end throughout the decade of the seventies and early eighties. However, experts began to realize that improvements were beginning to plateau and that additional improvement would require isolation and remediation of diffuse sources of pollution. The CWA was amended in 1987 to include section 319. Section 319 addressed nonpoint sources of pollution (NPS) or pollution not traceable back to a specific pipe or point of origin. The 319 program would be guided and funded by the federal government through EPA regional offices. However, it would be driven and implemented by state government, through voluntary cooperation with local landowners and stakeholders. With this amendment, states were charged with developing and maintaining an assessment report (list of impaired streams and their impairments) and a management plan. Meanwhile, back in Oklahoma, men like John Hassell, Ben Pollard, Jim Leach and Dan Butler were out in front, laying the foundation for what would later become one of the leading 319 programs in the country. In 1993, the Oklahoma Conservation Commission was statutorily designated as the lead technical agency in matters of NPS pollution. Since that time, the Water Quality Division has been hard at work protecting the waters of Oklahoma and thereby its citizens, so that they can expect and continue to enjoy streams that are both fishable and swimmable. To borrow some famous words from a famous Oklahoman, now you know the rest of the story. Thank you to Megan Knight and Marykate Higginbothan for their research on the topic, and to Leonard Moore for his contributions.  Blue Thumb staff and volunteers are currently monitoring around 110 sites. With some of those sites on the same creek, there are around eighty streams under the watchful eye of our programs. These creeks are found across the state, for example, the 2017 winter quality assurance sessions covered creeks in twenty different counties. Each and every one of these creeks is unique in its own way. Some are wide and deep, resembling a river more than what one might think of as a “creek.” Others are small, narrow and shallow, meandering through the landscape while receiving little notice from the human population. Recently, I was given the chance to begin monitoring my own creek, right here in Oklahoma City. Guy James Creek is likely very familiar to those who live around it, although it’s uncertain how much they actually think of the water flowing there and its quality. While it’s not very wide, it cuts a deep path through the middle of Edgemere and Guy James Parks, which are part of the Edgemere Park Historic District, listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The lovely neighborhood surrounding the parks is filled with brick houses in a number of different architectural styles, ranging in size from small homes to mansions. Front lawns and back yards of a residential neighborhood could, we might guess, contribute to runoff getting into Guy James Creek. Another contributing factor is the streets which border the park on all sides, 32nd on the south, 36th on the north, Hudson to the west and Harvey on the east. Not helping matters is the landscape of the parks themselves, mostly small groupings of trees, scattered around the gently rolling, grassy green hills. Along the banks of the creek, there is little to no riparian area, and the grass appears to be mowed right up to the edge of the creek. The area is not what could be called heavily wooded. All of these factors make the creek an excellent candidate for monitoring and it has been monitored by Blue Thumb volunteers in the past. A volunteer at another creek told me recently that when selecting a creek to monitor, she had hoped that maybe she could find a creek with a problem to solve, with something wrong that she could help to investigate and fix. At first glance, Guy James Creek seems like it might be that kind of creek. During the monitoring of the creek between 2014 and 2016, there were some results which seemed to support that theory. For example, a fish collection was completed on Guy James during the summer of 2014. Over the 400 meters or “quarter-mile” length used for the collection, only three fish were found and they were the same species, Green Sunfish, which is “known to tolerate turbidity, siltation and elevated temperatures,” and able to range from “moderately intolerant” to “tolerant,” according to the EPA’s An Introduction to Freshwater Fishes as Biological Indicators. One species and three fish is quite a difference from creeks in the same ecoregion (Central Great Plains) where we’ve found, on average, 596 fish representing thirteen different species. In another instance, an unusually high reading for Ammonia was found during a test in 2015. The water was sampled around ten o’clock in the morning on July 14th, right in the middle of summer. Blue Thumb staff took action at that time, contacting the Department of Environmental Quality about the high reading. As far as I’ve been able to tell, no cause for the high level of Ammonia was determined. This seemed to be an outlier, as the reading was normal a few months prior and a few months after the high reading. Similarly, when I tested the water myself two months ago, during my first monitoring session, I discovered an extremely low reading for dissolved oxygen. It was close to zero for a creek that has historically hovered around eleven-to-fourteen milligrams per liter. This water was also sampled in the morning, on March 27th. With the water temperature at fourteen degrees Celsius, the oxygen saturation was a very low seven percent. Recent tests have revealed that the oxygen level has gone back up to typical and healthy levels. Looking back, nothing else unusual happened during that late March round of testing. All of the other test results were within normal parameters. Nothing seemed out of the ordinary at or around the creek while I was there, deepening the mystery around what caused that extremely low level of oxygen. These kinds of test results can be fascinating (and alarming) and can lead to further testing and investigations. I’m looking forward to testing Guy James Creek again over the coming months, to see how things change (or don’t). I will also delve more deeply into these chemical tests in a future blog, providing more insight into what, exactly, we’re testing for and what the results mean. Stay tuned!  Early in my time here, somebody mentioned an upcoming event that I would attend called Fish School. I wondered, “What exactly is Fish School??” As you might guess or imagine, it is exactly what it sounds like, an opportunity for the Blue Thumb staff to spend a few days having an immersive and intensive learning experience about our local freshwater fish. As part of our biological collections, Blue Thumb performs fish collections every summer, rotating the location so that each region of the state is visited every four or five years. These collections include our volunteers, who help with using a seine to catch the fish as well as taking note of the stream’s habitat. Fish School provides an annual refresher course to the Blue Thumb team, providing an opportunity to see, touch and identify numerous species that might be encountered during fish collections. Being able to identify fish is an essential part of the fish collection process and also increases the excitement for volunteers who may have never seen these fish before. Like some of our volunteers, I went into Fish School with little to no knowledge of our local freshwater fish. A few weeks prior to the event, I did start studying, on the advice of one of our resident fish experts, Nathan Carter. Nathan is one of our water quality monitoring specialists and is among those who organize the agenda of Fish School. He recommended if I wanted to prepare beforehand, I should study species of sunfish, gar, suckers and catfish. The preparation definitely came in handy later, when it was time to start getting to know the fish face-to-face. Fish School began on Monday, when we arrived at Robber’s Cave State Park, where we all stayed at their hotel-style lodge with a spectacular view of the surrounding hills. After checking in, we settled into the conference room for some PowerPoint presentations about fish anatomy, sunfish and the habitat assessment process. After the review (or, in my case, seeing it all for the first time), we headed to nearby Fourche Maline Creek and talked through the habitat assessment technique that our monitoring staff uses whenever they visit a stream. We were originally scheduled to talk about bug collections and other topics, but the recent rains made the creek too high and too fast. That may have been good for me, since it provided me with more time to spend in the creek, learning about habitat assessments. Along with Nathan, monitoring specialists Jason Ramming and Leonard Moore, as well as Blue Thumb’s own Candice, we walked up the stream providing lots of habitat lessons and information along the way. The immersive educational experience continued on Tuesday, as we all drove to Black Fork of Poteau River for more discussion of habitat and our first look at fish species. It was a gorgeous drive through rolling green hills, forests and farmland, right to the river’s edge. We split up and began collecting fish, some of us on foot, using a portable electric-shock device and nets, while others rode on a boat also equipped with an electric-shock device. This allowed us to stun the fish just for a moment, catch them in a net, examine them and release them back into the water alive and well. Doing this kind of fishing, both on foot in the creek and from the boat, was a totally new and fascinating experience for me. As a whole, it was a pretty amazing day, personally, especially since I was the least experienced fish person in the group. I got to see multiple kinds of gar, sunfish and bass, along with a number of different darters and minnows, all for the first time. More firsts happened on Wednesday, as we went to another spectacular spot, Holson Creek. There, we did more fishing, although I didn’t take part in that as much as I had the day before. I did get to do some seining for fish with another of our monitoring specialists, Wes Shockley, who also helped me prepare for the upcoming habitat assessment test. During our time at that creek, we also had our discussion on bug collections and continued to find and examine various fish species. Later that day, we went back to Fourche Maline Creek for the habitat assessment test, a way for everyone involved to make sure they are looking at and describing stream habitat in the same way. Kim and Jean helped me along the way as we walked two hundred meters of stream, taking note of everything from water depth to riparian area width to the materials making up the creek’s bottom. Similar to the habitat assessment test, the fish exam on the final day of Fish School is a way to test everyone’s ability to identify fish and ensure everyone can identify different species correctly. For me, it was definitely a challenge, although I had been studying and preparing, so I definitely did better than if I had gone into it completely cold. It was a beautiful day to be at the water and, for me, a true learning experience. It also only scratched the surface of everything I need and want to continue to learn about. Fish School was four days of connecting with nature and the outdoors, being immersed in all its beauty, and learning about many of its inhabitants. And it’s just the beginning of the enormous education this job will continue to provide. In my last post, I mentioned that my job started right in the middle of winter bug collections, providing a fantastic opportunity to crisscross the state, visiting streams and meeting volunteers. The beginning of my time here also gave me the chance to attend three different Blue Thumb volunteer trainings, another integral part of what we accomplish across the state through the work of our dedicated and inspiring volunteers.

Late January saw the Blue Thumb staff assembled in a classroom at Oklahoma City University. A large group of potential new volunteer monitors arrived for the training, quite a few of them already working in an environmental or educational profession. During that training, I had the chance to experience it as a volunteer, going through the process in the same way the volunteers do (and will soon begin monitoring the creek that we visited during the training!). A second training happened in February in Pawhuska and was attended by members of the Osage Nation, as well as members of other tribes and the local community. It was especially exciting to see the number of young people who attended the training who were interested in getting involved in protecting the environment. Quite a few young people also attended the third training, in Beaver in early March, which gave me a chance to visit the panhandle for the first time. Two-day training sessions like these are an outstanding way for local citizens to become involved in their community by working alongside Blue Thumb to monitor and educate about a local stream. The volunteers are our eyes and ears on a stream and also the way we spread our message of stream protection through education across the state. One of the goals of the training is to empower people to protect their stream by educating about it in their town or region; whether in schools, local community events such as Earth Day or Natural Resource Days, presentations to local service clubs like Rotary and Kiwanis, exhibits at the local public library, tables in front of Walmart, or just about anything else they can come up with. We couldn’t do it without them. An informal icebreaker gets things started on day one of training and gives everyone the chance to meet and get to know each other a bit. After that, we provide the volunteers with a presentation that introduces them to Blue Thumb and what we do. It also gives them an idea of some key concepts that they’ll be thinking about in relation to their stream and fills them in on how, exactly, their work could directly impact the health of the creek they monitor. Presentations led by Blue Thumb staff cover safety concerns related to creek monitoring and the data sheet that volunteers fill out when they visit their creek. During most of the first day, attendees are introduced to some of the educational tools and activities that they can utilize to teach others about water quality, pollution, runoff and other issues. Usually included are a demonstration of an Enviroscape model, a rainfall simulator and a fun and educational Project WET activity. The first half of day two may arguably be the most fun part of the training, as we take the entire group of volunteers out to a local creek to demonstrate the kind of work they will be doing. Depending on how many staff members are present, how many volunteers there are, and what the creek is like, we may split into smaller groups. Each group gets to participate in a macroinvertebrate collection (bug kicking) and using a seine to look for fish, just like at our summer fish collections. Groups are then instructed on how to do the only part of the chemical tests that must be done creek-side, preparing a sample of water to be tested later for dissolved oxygen. We also cover the monitoring data sheet and the procedure for testing the water’s clarity. Others would argue that it’s actually the second part of the day that’s the most fun, when volunteers get to conduct the other chemical tests. These tests for dissolved oxygen, nitrate/nitrite, orthophosphate, chloride, pH, and ammonia are conducted every month by volunteers. During the training, they get to go through and complete each test, with the help of Blue Thumb staff members. It’s a lot of fun and a great introduction to the kind of easy and exciting chemistry that volunteers can do at home with their creek water. The results are immediate and sometimes surprising, giving everyone a chance to see firsthand and discuss the quality of the creek we all just visited. Blue Thumb trainings are completely free of charge, open to all, and are great for teachers, middle and high school students, landowners, retirees, professionals, 4-H leaders and members, or anyone with an interest in clean water! Check our website and Facebook page for future training dates. We hope to see you at one soon! Blue Thumb’s goal of monitoring streams to make sure they’re healthy is accomplished with a three-pronged approach, biological, chemical and physical. Most important among these is biological monitoring, achieved through summer fish collections and twice-a-year collecting of creek-dwelling bugs. I was lucky enough to start my new job right in the middle of the winter bug collection season. This has given me the chance to crisscross the state with Kim, Candice and Jeri, meeting volunteers and visiting a wide variety of creeks, in both rural and urban settings. It’s been an adventure and an opportunity to learn something new every day as I’ve discovered the diversity of the towns, people and waterways of our region. I’ve gotten to visit Lawton, Tahlequah, Tulsa, Norman and many other communities during our quest to find the benthic macroinvertebrates living at the bottom of creeks and streams.

What is a benthic macroinvertebrate, you ask? The word “benthic” means “of, relating to, or occurring at the bottom of a body of water” (the lowest level of a body of water is known as the “benthic zone”). Micro is a well-known term, meaning tiny or extremely small. Macro is the opposite, meaning large in scale or scope. It’s something we can see with our naked eye, without the help of something like a microscope. And finally, invertebrates are any creatures without a backbone. So, benthic macroinvertebrates are species that live at the bottom of a creek or stream which have no backbone and are large enough that we can see them with the naked eye. The next question you might ask is, why are they so important? Benthic macroinvertebrates are important indicators of the health of a steam and the quality of its water. This is due in part to the fact that some species can live in degraded, polluted waters, while others cannot. When we collect these diverse bugs, we are looking for and hoping to find those species that can only survive in clean, unpolluted waters. If there are many of them, and a diversity of types, it’s a good sign that the water is likely to be healthy. On the other hand, if we are not finding those intolerant species and only collect bugs that are very tolerant of pollution, it may be an indication of something deteriorating the quality and health of the water and the habitat it provides. These species are also excellent indicators of that habitat’s health because they spend most or all of their lives in one place and cannot easily escape pollution, unlike fish, for example, who can swim away. Over time, generations of these creatures provide a long-term view of the stream, unlike the momentary snapshot of a one-time chemical test of the water. As we observe how the bug populations change with time, including population density and diversity, we can discover how the stream as a whole is changing. Along with our volunteers, we find spots in the creek where there’s a riffle, a shallow section of the stream where the water is flowing rapidly over the rocks, gravel, sand, etc. Downstream of the riffle, one person holds a kick net with one end wide open to catch as much as possible in the net as water flows in. The other particpants then stand in the riffle and kick up as much of the stream bottom as they can. This disturbance of the creek bottom causes all of those tiny creatures living on and under the rocks, sticks, leaves, etc. to get caught up in the current and flow right into our waiting net. We do this three times, in three different spots, preferably three areas with some variety to them, perhaps in the velocity of the water or the type of material on the creek bottom. After each kicking, the sample is gathered into a bucket so that it can be combined. A portion of that then goes into a mason jar and preserved in alcohol until we can pick through the sample at a later date. The entire process is fun and fascinating and a great way for volunteers to get an even better idea of their stream’s health. They can see for themselves just how much life is actually in their stream and how diverse that life is (or isn’t). These bugs tell us a lot and become an essential and important part of the high-quality data Blue Thumb provides to Oklahoma and the Environmental Protection Agency. Collecting benthic macroinvertebrates to study water quality has been around for many years and is practiced around the world. The Environmental Protection Agency provides some great information on water quality monitoring - https://www.epa.gov/national-aquatic-resource-surveys/indicators-used-national-aquatic-resource-surveys Benthic macroinvertebrates are also an important part of freshwater ecosystems and the food chain. Read more about the roles they play in this article from BioScience: https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/article/49/2/119/239602/The-Role-of-Benthic-Invertebrate-Species-in One of the best things about my job with Blue Thumb is the chance to explore and experience many different parts of Oklahoma. While traveling over the past month, I was struck by the diversity in landscapes during two trips, one to Enid and the other to Tahlequah. The first trip, on my way to work at the KNID AgriFest in Enid, 100 miles north of Oklahoma City, took me through the Central Great Plains, an expanse of grassland known for being very flat with sparse vegetation, among other qualities. As I drove through it, it struck me how very wide-open it is, much different from other parts of the country I’ve lived in, such as New England, where I was born and raised. Here in the Great Plains, the landscape offers an entirely different kind of experience. The spectacular yellows, browns and golds, broken up by the occasional field of lush green, stretch as far as you can see, dotted by the sporadic form of a dark brown tree stretching skyward.

Not long after that adventure, I joined Jeri on a trip to Tahlequah and the Illinois River, to check out a riverbank restoration project. The drive to the northeast corner of the state offers a gorgeous view of a landscape that’s much different but just as beautiful as the Great Plains. We drove through the Cross Timbers and the Central Irregular Plains, two more of the many regions found in this ecologically diverse state. The Cross Timbers is a transitional area between Central Great Plains and the much more forested regions to the east. As we drove through, the change was clear as the scarce vegetation gave way to more hills and heavily wooded areas, with lots of trees, mostly bare from winter, but some still very green. We then passed into the Central Irregular Plains ecoregion, a north-south strip of prairie that separates the Cross Timbers from the heavily forested ecoregion which was our final destination, the Ozark Highlands. Upon entering this ecoregion, the scenery became a bit rockier, with more hilly terrain covered by a majority of still-green trees. As we wound along one particular road, approaching the Illinois River, I remarked to Jeri that it reminded me of some of the mountainous country roads I’ve experienced while traveling other parts of the country. It’s another remarkable part of Oklahoma, an area I look forward to spending more time exploring on my own in the future. It was also a fantastic introduction to the strikingly beautiful Illinois River, which we got to visit on a picture-perfect weather day. Definitely something to add to the long list of places I want to get better acquainted with. The natural diversity of this state is extraordinary and the chance to experience this kind of variety in nature is one of the many great things about living here. Check out more information on Oklahoma’s ecoregions at the links below and then explore them for yourself. http://www.travelok.com/article_page/oklahomasdiverseecoregions http://forestry.publishpath.com/websites/forestry/Images/OK%20Ecoregions%2011x17.pdf As an adult, the first day at a new job isn’t much different than the first day of school when we are kids. The day is filled with excitement, nervousness and the unexpected. Most importantly, it’s a new beginning, the first step of an exciting new journey. My first day, and first two weeks, as the Conservation’s Commission’s new Blue Thumb Educator have been no different. It has been a whirlwind two weeks that included an ice storm, a farm show and the warmest of welcomes from everyone here at the Conservation Commission.

While I’ve had a number of jobs in my life, few have gotten off to such a busy and exciting start. During a Blue Thumb staff meeting on day two, I discovered that being busy will be the rule, not the exception, as we planned the upcoming weeks. There will be Blue Thumb Trainings in Oklahoma City and Pawhuska, an Environmental Education Expo, a moving day at the Bristow office, and a number of opportunities to get out into the field with my new Blue Thumb teammates. Two days later, I was on the road for the first of these mini-adventures, on my way to Enid for the KNID AgriFest. The two-day event was not dampened by the weekend’s ice storm and provided an amazing opportunity to meet lots of people and talk to them about how soil health directly relates to and impacts stream health. Of course, it was also a great educational opportunity for me, as I began the process of learning as much as I can about the Commission, Blue Thumb and all of our important work. That learning process continued in the second week, with more time spent in the office. This time was largely spent researching both the work of the Commission/Blue Thumb and the natural resources of my new home state. From the various ecological regions to the scenic rivers to the fish species that call those rivers home, there’s a lot to learn. At the end of the week, all of us on the Blue Thumb team had the chance to participate in a Project WET (Water Education for Teachers) training. As we continue to educate community members, young and old, about water quality, the skills, knowledge and tools gained through this training will prove to be invaluable. Upcoming days will include getting out in the field with Jeri and Kim, providing me the chance to start experiencing the extraordinary landscape around us and begin meeting our amazing volunteers. I look forward to really starting this new adventure, and also look forward to sharing the experience with all of you. |

The Blue Thumb Blog

Archives

July 2018

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed