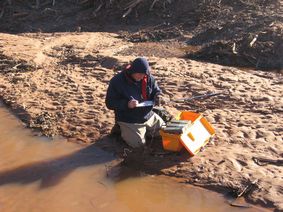

Water Quality Specialist, Wes Shockly is out in all kinds of weather checking on Oklahoma's water resources . Water Quality Specialist, Wes Shockly is out in all kinds of weather checking on Oklahoma's water resources . Over the past six months, there have been so many things to learn. Much of this job is new to me and has provided me the opportunity to find out about and experience many new things. One thing I have become more aware of is the Section 319 program, part of the federal Clean Water Act. This program provides money to states for initiatives that focus on water pollution and water quality, including our own Blue Thumb program, which is primarily funded by 319 money. The Clean Water Act and subsequent Section 319 program are part of a long history in this country of growing awareness and interest in environmental issues, including water quality and pollution. For more on that history, and what it has meant to us here in Oklahoma, we turn to Wes Shockley, one of our water quality monitoring specialists, a native of Oklahoma who has quite a bit of history himself with the Conservation Commission and the Water Quality Division. The turn of the twentieth century marked a time of explosive growth in industry. Many of these factories required large quantities of water, either for the manufacturing of their product or for the cleaning and cooling of their equipment. So it was only natural that these businesses were located near large supplies of fresh water. Perpetual containment of this waste water was not practical. The convenient answer was to simply return the water to its source in its new form, complete with oil and grease and a myriad of other chemical byproducts of the various manufacturing processes. This practice continued, principally without thought or regulation, for decades. In 1962, Rachel Carson authored Silent Spring. Her award winning work chronicled the effects of the pesticide DDT on a population of song birds and other wildlife and it spawned a national increased sensitivity to the natural world. Then, in 1969, the Cuyahoga River, in Ohio, caught fire. The river was so polluted at this point that its burning had become commonplace, but for some reason on this occasion, the story garnered local press coverage, complete with photos. Soon, a few big publications and news outlets picked up the story and it went national. Seemingly overnight, the entire country was metaphorically on fire with a new consciousness of and responsibility to the environment. This momentum continued to build and compelled President Nixon, on Dec. 2, 1970, to sign an executive order establishing the Environmental Protection Agency. (EPA). In 1972, amid growing public concern, congress passed the Clean Water Act (CWA), placing regulations on municipal and industrial dischargers and creating the NPDES permitting system, which was designed to track dischargers and monitor the quantity and quality of their effluent. The overarching goal of the CWA was that all surface waters of the U.S. should be fishable and swimmable. Good progress was made toward that end throughout the decade of the seventies and early eighties. However, experts began to realize that improvements were beginning to plateau and that additional improvement would require isolation and remediation of diffuse sources of pollution. The CWA was amended in 1987 to include section 319. Section 319 addressed nonpoint sources of pollution (NPS) or pollution not traceable back to a specific pipe or point of origin. The 319 program would be guided and funded by the federal government through EPA regional offices. However, it would be driven and implemented by state government, through voluntary cooperation with local landowners and stakeholders. With this amendment, states were charged with developing and maintaining an assessment report (list of impaired streams and their impairments) and a management plan. Meanwhile, back in Oklahoma, men like John Hassell, Ben Pollard, Jim Leach and Dan Butler were out in front, laying the foundation for what would later become one of the leading 319 programs in the country. In 1993, the Oklahoma Conservation Commission was statutorily designated as the lead technical agency in matters of NPS pollution. Since that time, the Water Quality Division has been hard at work protecting the waters of Oklahoma and thereby its citizens, so that they can expect and continue to enjoy streams that are both fishable and swimmable. To borrow some famous words from a famous Oklahoman, now you know the rest of the story. Thank you to Megan Knight and Marykate Higginbothan for their research on the topic, and to Leonard Moore for his contributions.

0 Comments

|

The Blue Thumb Blog

Archives

July 2018

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed